PETE #3 The Story of Unification

Münchner 'Leuchtkugeln', 1848. Title - The German Unity Tragedy in One Act (‘Die Deutsche Einheit. Trauerspiel in einem AUfzug’)

Source - Leuchtkugeln (via https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Question)

The unification of Germany that took place in 1871 was not a certainty.

To help give you a sense of how unlikely it was, imagine that you woke up in 2010 in Britain and someone said to you that within a decade of that day the first coalition government since the war would have governed for a full five years, Scotland would have been a week from independence and breaking up the 300-year union, there would have been three general elections in five years, the UK would have left the European Union, two prime ministers would have governed having never won elections and the entire country would be legally obliged not to leave their own homes for two months. And… there would be this growing sense that social media may not be a totally a good thing.

Doing a quick bit of maths I reckon the odds were longer for German unification.

The reasons why it happened and happened then has naturally been hotly contested. I will illicit two primary arguments below. I will say before I do, that I love how well this debate frames two fundamentally different ways of understanding events, both big and small. One explanation puts a dominant historical figure in the centre and the other argues that bigger longer forces were at play.

As the picture below illustrates, before German unification central Europe still had around 39 states with Prussia the dominant power in the North, and Austria the dominant power in the south. I will elaborate in a further blog about the cultural aspects to the unification but it is enough to say at this point that many of those who spoke German and may well have thought of themselves as German, did not end up included the state that was realised in 1871.

Diagram of the German lands pre-unification.

Bismarck was installed as the minister-president of Prussia by the Prussian Kaiser, Wilhelm I, in 1862. Within 11 years he would be painted in the Palace of Versailles declaring the Prussian Kaiser as the German Emperor. His account, written in his memoir decades later, of the intervening years tells the story of masterly statesmanship and the deliberate planning and delivery of the unification. In fact, Bismarck’s reputation has now come to be largely defined as a very talented opportunist. [1] I largely agree with the view that Bismarck pursued the narrow interests of his own Junker class in a bid to shore up a decrepit Prussian monarchy that he believed in. In so doing he scaled up throughout the decade from a local conflict with Denmark over Schleswig-Holstein in 1864, to a German showdown with Austria in 1866 and finally the decisive regional war of 1870 with France.

Painting of the Proclamation of the German Empire in 1871.

Source - Anton von Werner - Museen Nord / Bismarck Museum: Picture

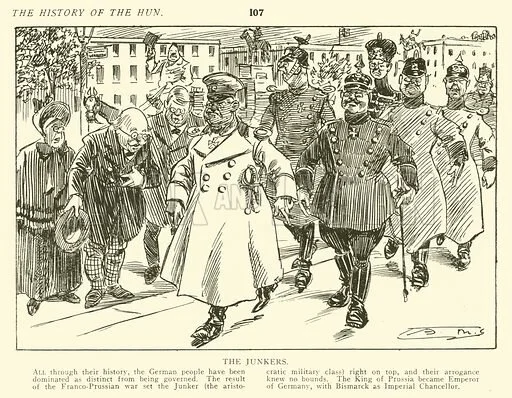

When I say he was protecting the Junker class, I’ll give a little context about what I mean. I am of the view that I would not have liked a Junker if I met one. They combined a rotund insouciance with a stomping adoration for Prussian militarism and silly helmets. That said, of the many opinions about Bismarck some of the later historians have shown his more humorous side effectively. In particular Christopher Clarke quotes a nice piece from one of Bismarck’s letters mocking himself and his own class, ‘I shall get pissed on the king’s birthday and cheer him vociferously and the rest of the time I shall sound off regularly’.[2] So perhaps there is more in common with a Junker and most dads in Britain than I had allowed for.

The Junkers. Illustration for The History of the Hun by Arthur Moreland (Cecil Palmer and Hayward, 1917).

Source - https://www.lookandlearn.com/history-images/M515453/The-Junkers

The unification of Germany was not Bismarck’s goal and did not happen as the result of an authentic popular nationalist movement. Bismarck’s agenda was driven by a succession of Prussian crises centred around parliamentary calls for democratic representation and national German unity. Bismarck was able to sate the insurrection internally in Prussia with victory over the other regional powers, most notably France. He did this by cynically courting and exploiting a growing sense of German national sentiment in Prussia, regardless of the wishes the of states around it who eventually fell within the Prussian-led German empire.[3] The unification driven not by some groundswell of German sentiment towards Prussia.

If you have ever heard the phrase that ‘war is merely the continuation of policy by other means’, a theory created by another German called Von Clausewitz, then Bismarck and his generals have come to epitomize that approach.[4] Bismarck was the lucky beneficiary of a number of reforms to the military by appointments that predated him. Most notably the reforms enacted by Roon and Moltke meant that when he turned to his army to effect policy decisions and regional diplomatic crises, they were in a position to effect his limited policy goals. Through these limited conflicts Bismarck was able first to establish hegemony in northern Germany by defeating Denmark in 1864, then in seven weeks to inflict decisive victory over Austria in 1866 and thereby demonstrate Prussia’s supremacy over the majority of the 39 states.[5] In 1870 an old fashioned dispute over the succession of the royal throne on Spain was fashioned by Bismarck into a diplomatic crisis that he used to justify invasion of France. Thanks to the military reforms of Roon and Moltke the war was won in weeks and soon after Bismarck and Wilhelm proclaimed the German Empire in the Palace of Versailles. This Germany has been termed the Kleindeutschland, ‘small Germany’, because of its exclusion of Austria.

An inhabitant of Berlin in 1840 would have struggled to recognise his own city fifty years later. Prussia went through one of the most rapid processes of industrialisation ever. Comparisons with China’s experience in the twentieth century may give a modern-day approximation. Industrialisation, mechanisation, electrification and the creation of the urban poor took around a century in the UK but was achieved within only a couple of decades in cities such as Berlin.[6] The streets went from muddy and horse-drawn thoroughfares to having electric streetlights and the motor car. Pharmaceutical giants such as Bayer, Braun, industrial powerhouses like Thyssen, Krupp and Daimler were all founded in the period.

The Old Berlin City Hall (Johann Wilhelm Brucke (1800 - 1874), 1840.

© Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz / Hermann Buresch

Berlin, Alexanderplatz, circa 1890 (source unknown)

Germany’s industrialisation was a coincidence of many factors of which some were within the control of the participants and some were not. Reforms imposed by Napoleon during the occupation at the start of the century allowed for privatisation of farming which freed up labour, broke down feudal hierarchies and encouraged cross-border trade of agricultural goods. The result was a more individualised and market-orientated rural economy. Within decades metal railway tracks were snaking across the countryside with British steam railway technologies propelling forward a rapid acceleration of a new industrial economy.

In 1834 a customs union was signed between many of the states in Germany to manage their tariff and duty systems in order to make it easier to trade and move goods around across the borders. This group grew throughout the next four decades with Prussia as the architect to eventually include most of the German states, although notably not Austria.[7] The Zollverien, as the customs union was known, started primarily to alleviate burdensome paperwork and to allow easy access between Prussia’s central territories and its industrial territories in the northwest of Germany (near the French border) which were separated (see map).

The Zollverein gained its own momentum as a driver of industrial growth and became a self-serving policy in its own right. Each of the member states started with their own motivations for joining but the governors and rulers primarily saw this as an opportunity to gather more taxes from increasingly wealthy populations. Many were also brought into line with ‘arm-twisting’ from Prussia as she sought to exert her dominance regionally and at the expense of Austria’s weaker agrarian economy.[8]

As the trade connections grew the new generation of merchants and industrialists, not to mention the new class of wage earners, came to represent their own influence on policy and the promotion of closer economic union. The results of this trend throughout the nineteenth century was a unity and collective wealth throughout the German lands that had never been experienced before. It was led by Prussia at the exclusion of Austria and it included a new, vocal and educated constituent in society.

What I hope that that I have shown here is that the Germany that was created in 1871 was a precarious object. She had been manipulated into existence by Bismarck without any great popular mandate but instead through military prowess. To compound this was a lurking economic might with its demographic dislocations and appetite of its own. When compounded by the geographical situation explained in my previous blog it seems to me that stage was well set for conflict.

To me this is a fascinating story of how economic, political and ideological forces can combine. Each component was likely acting for a combination of altruistic and selfish reasons but the net effect was an historical phenomenon that would shape the next 150 years and counting. I think it would be a little hollow to try and impose my version of what this means for the decisions that we need to make today. Some appealing parallels don’t seem to hold up – like the EU – whereas as others I think might, such as the cynical manipulation of earnestly held sentiments. But one conclusion above all seems to be unavoidable. That without sensible, moderate and open-minded pan-European policy-making it is only a matter of time before conflict erupts. When it does the institutions, politicians and economic balances that exist will determine just how grim the consequences are. Or, in other words, choices matter.

[1] A.J.P.Taylor, The Course of German History, (Hamish Hamilton Ltd., 1945), p.112-114

[2] Christopher Clarke, Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia 1600-1947, (London, Penguin, 2007), p.519

[3] Taylor, The Course, p.114

[4] Peter Watson, The German Genius, (London, Simon & Schuster UK Ltd., 2010), p.184-188

[5] Clarke, Iron Kingdom, p.542

[6] Edwin Redslob, Von Weimar nach Europa. Erlebtes und Durchdachtes [From Weimar to Europe: Experiences and Insights], (Berlin, 1972) pp. 28-30. Original German text reprinted in Jens Flemming, Klaus Saul, and Peter-Christian Witt, eds., Quellen zur Alltagsgeschichte der Deutschen, 1871-1914 [Source Materials on Everyday Life in Germany 1871-1914]. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1977, pp. 47-49.

[7] John Breuilly, The Formation of the First German Nation-State, 1800-1871, (Macmillan Press Ltd., London, 1996), p.21-23

[8] Clarke, Iron Kingdom, p.393